Reversing Covfefe.exe, Flare-on Challenge 11

Reversing the binary of 11 was easy, but it wasn’t meant to be hard. The difficult part was reversing the VM code that the binary runs. When implementing the VM I made a mistake in the code that caused me problems trying to sort out. When it checks the index at each loop I had “index < end”, when it should have been “index <= end”. This caused it to end prematurely.

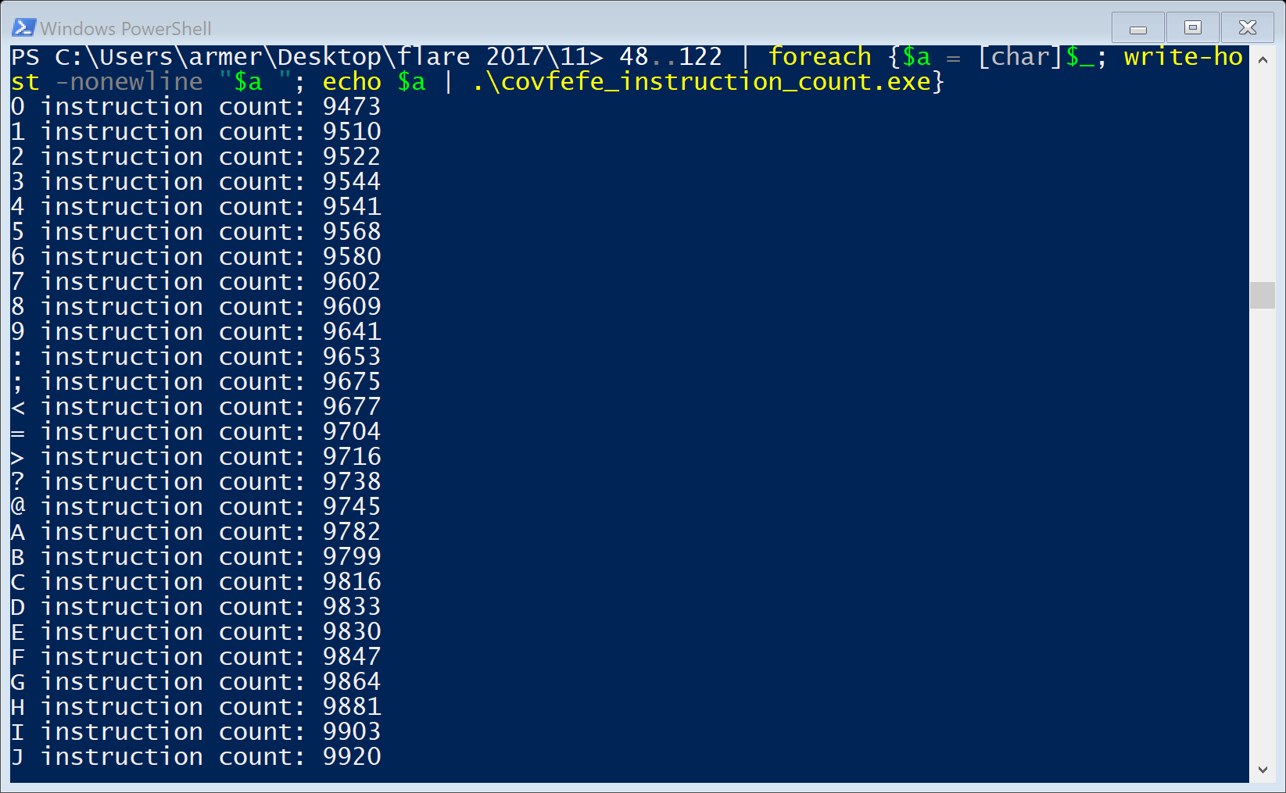

I needed a little help on this challenge and was given two approaches other people used. One was to output logs for the execution of the VM, which I was on the way to do. The other was to use a side channel attack to get the key. I was told the approach taken by Pierre Bourdon to attack Simple from PlaidCTF 2012 could be adapted here. I decided to try the side channel attack, since it seemed like an interesting way to get the key. Below is the count of instructions when trying the input 0 - z.

As the ascii code increased, so did the number of instructions. This was different that the expected output, from reading about Pierre Bourdon’s attack. I did not know enough of how the code worked to adapt it correctly. I decided to instead study the execution of the VM, and see if I can learn what it does. In this approach I rewrote the VM in C++ and added in code to output its execution into logs I could study.

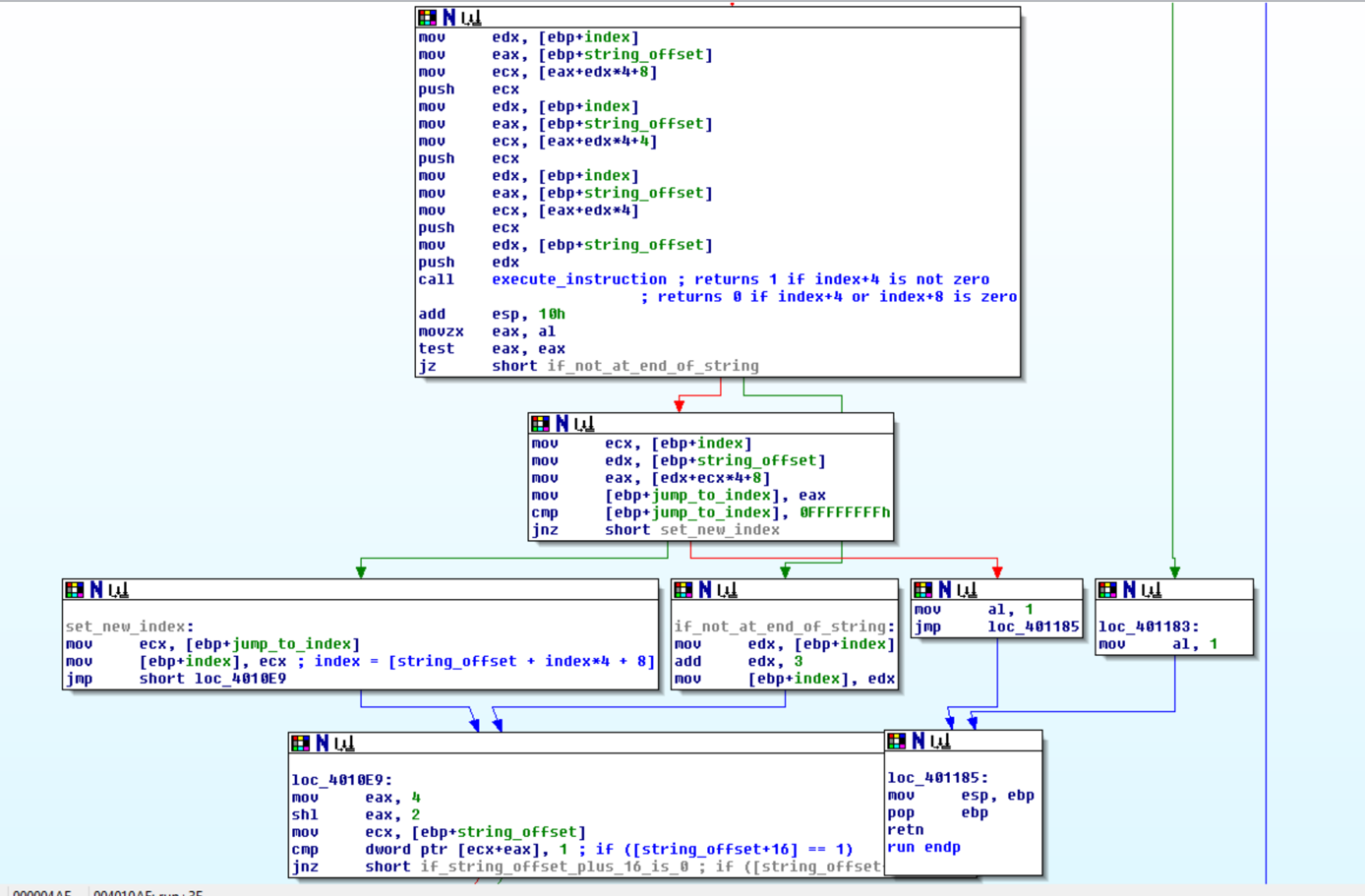

###How the VM worked### When the program is executed it calls a function and passes the address to the VM code, the start index, and the end index. It then checks to ensure the start index is before the end index and starts the executation loop.

On each loop the VM calls a function to execute the current instruction, which is made up of 3 ints. The index is multipled by 4, since an int is 4 bytes. Four and eight are added so that those indexes are pointing to the next two ints respectively.

After the executation the VM would then jump or go to the next instruction, depending on the result of the executed instruction.

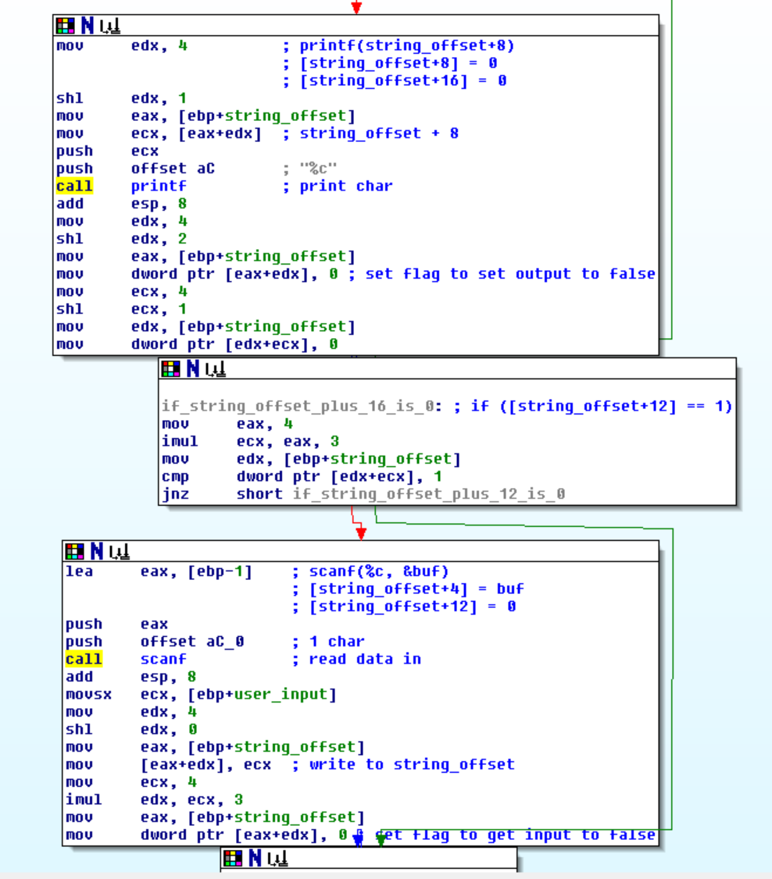

The VM would then check if index 16 == 1, if so then it would output the byte in index 8. Next, index 12 was checked and if it was 1 a byte was read and stored in index 4. This let me know the VM used index 4, 8, 12, and 16 as different registers. I could then watch these to learn more about what the VM code was doing.

run(*VM_code, end_index, start_index) { // mockup code

index = start_index;

while (index + 3 <= end_index) {

if (execute(VM_code, VM_code[index], VM_code[index+1], VM_code[index+2])) {

if (VM_code[index+3] == 0xFFFFFFFF) {

return;

}

index = VM_code[index+3];

} else {

index += 3;

}

if (VM_code[16] == 1) {

printf("%c", VM_code[8]);

VM_code[16] = 0;

VM_code[8] = 0;

}

if (VM_code[12] == 1) {

scanf("%c", &VM_code[4]);

VM_code[12] = 0;

}

}

}

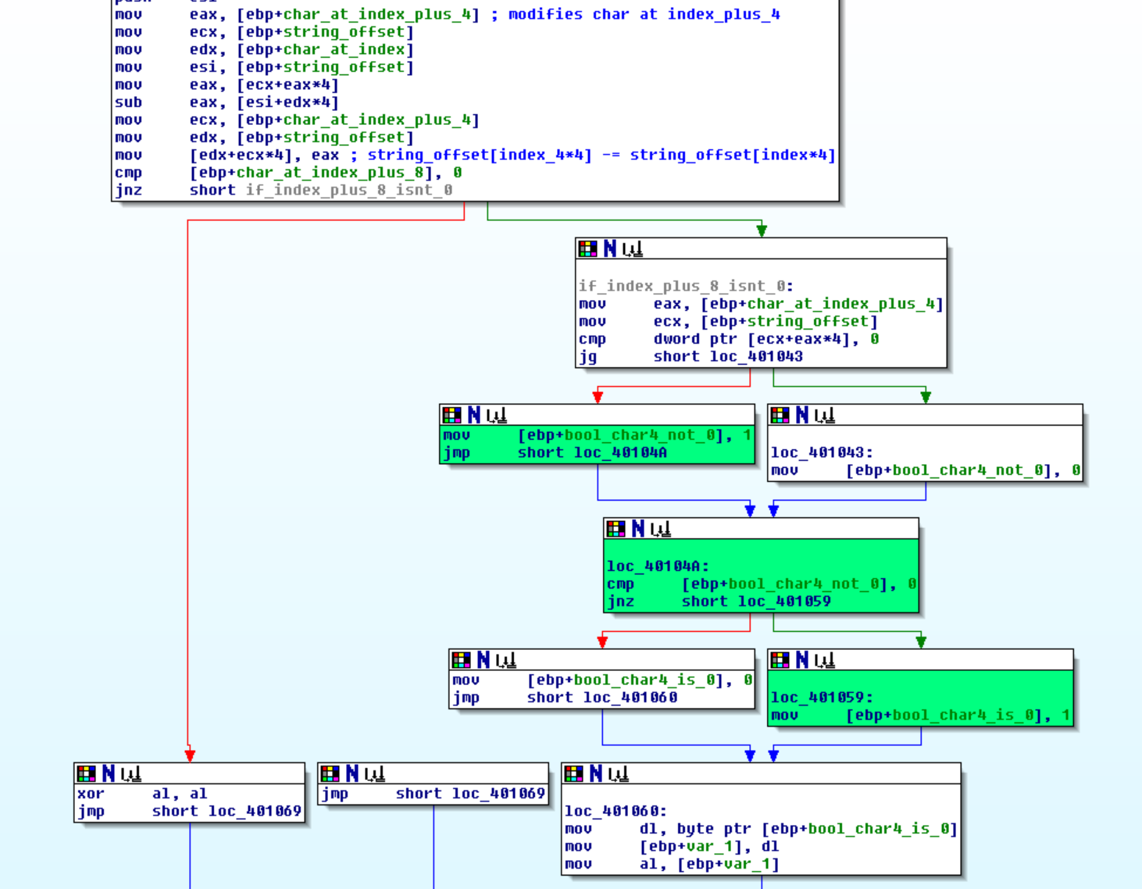

The VM only had one executation which was VM_code[int_2] = VM_code[int_2] - VM_code[int_1]. VM_code[int_3] is checked to see if it not zero. VM_code[int_2] is then check if not greater than 0, if this is true then the executation function returns true. This in turn triggers the VM to jump to address VM_code[int_3].

execute(VM_code, instruction_1, instruction_2, instruction_3) { // mockup code

VM_code[instruction_2] = VM_code[instruction_2] - VM_code[instruction_1];

return (instruction_3 != 0 && !(VM_code[instruction_2] > 0));

}

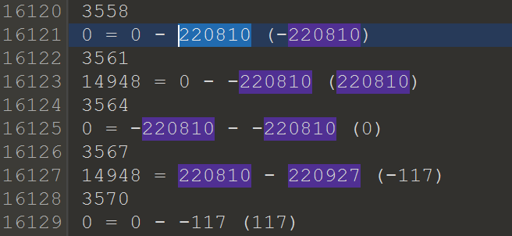

I added a print statement to print the current index, current instruction, and if it jumped. I was then able to use this output to trace the executation of the VM code and determine what it was doing. Below is an example of the logs from the execution of my code.

...

1139

0 = 0 - 0 (0)

jump 1143

4716 = 0 - 0 (0)

1146

...

###Tracing the logs###

From reversing I knew a few useful things that helped me out. I knew that when it writes output to the screen it sets index 16 to 1, and when it reads it sets index 12 to 1. I made two logs of the execution of the VM on similar input.

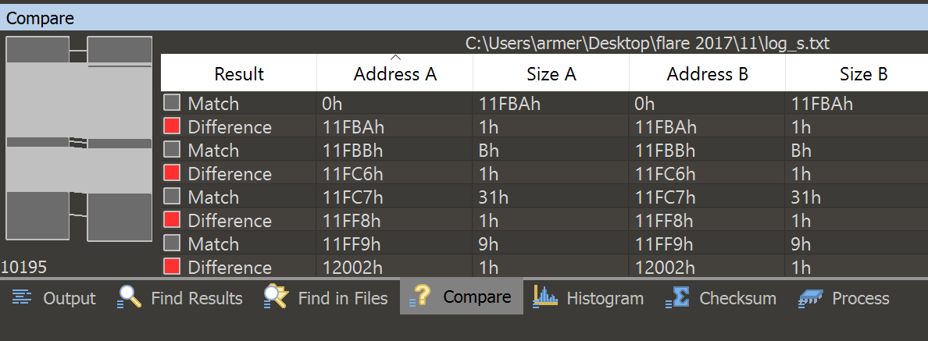

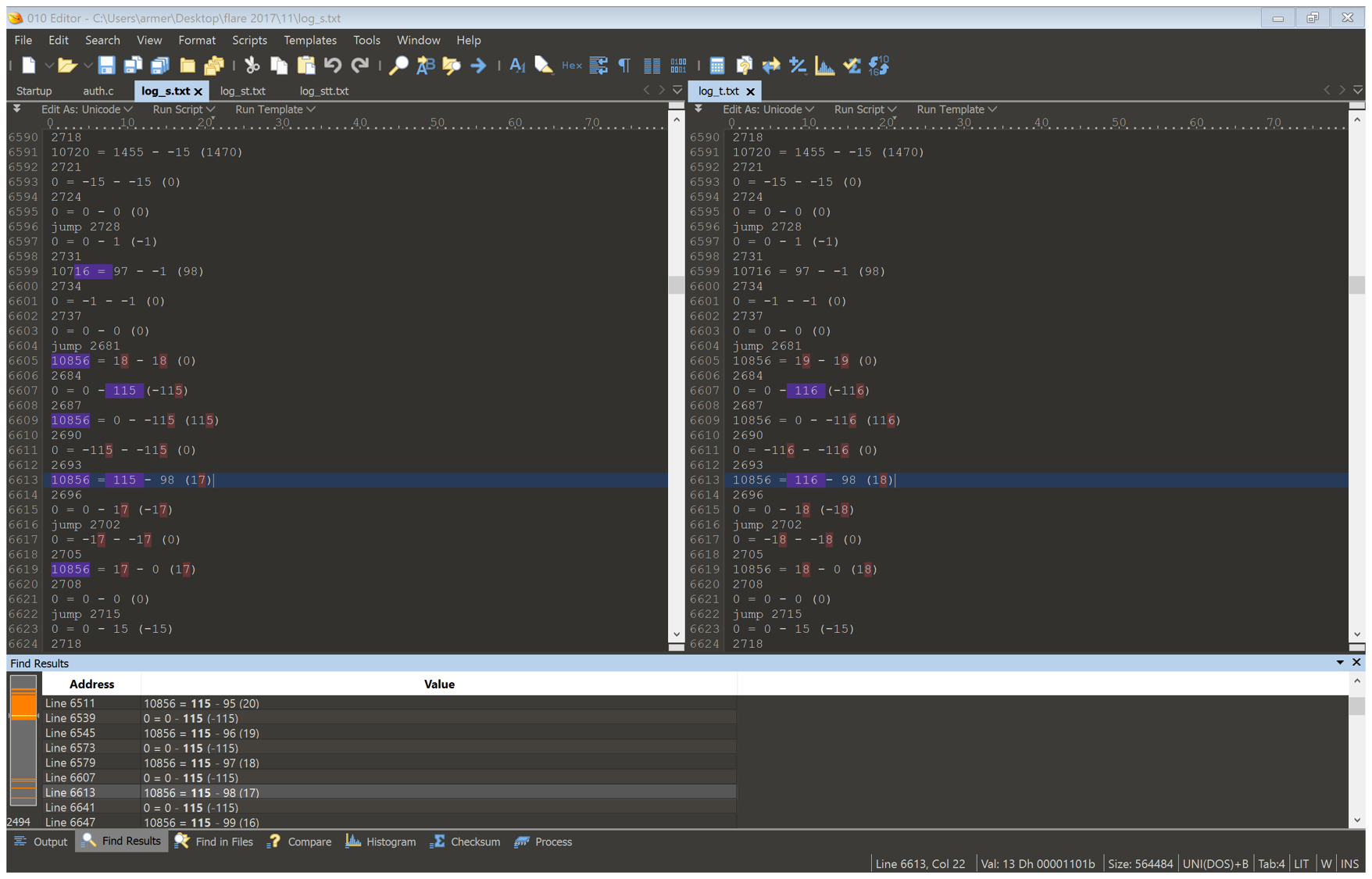

I used logs from input s and t and opened 010 editor to find the difference of the two logs. The dark gray is when the text matches, and the light gray is when that line only partially matches.

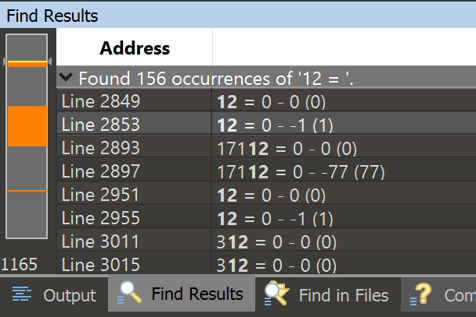

This showed me where the execution of the VM differed based on the input, but I still had trouble finding what I needed. So then I used 010 to find all references to “16 = 1 “, which told me where in the logs the VM was about to output data.

I then searched for “12 = 1 “ and found where it reads user input.

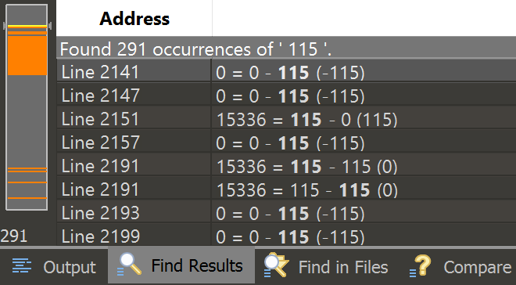

Searching for the the ascii code of s (115), showed me where the VM referenced the char I had input.

There was a gap in the code between where the user inputs string, and where the error message is output. So this was the area I should focus my search to. Following the difference of the two files showed me that after the user’s input is read it loops until the doing something until the loop index is equal to the char that was read in.

This caused the difference in instructions executed that I saw earlier. I compared after the jump on both files and found an interesting string, a little bit before the error code.

14948 = 220810 - 220927 (-117) (log_s.txt)

The number being subtracted is different, but 220810 is the same. This indicated that it might be part of the encoded string. I search for it in the binary and found data that resembled it.

###finding the encoded flag###

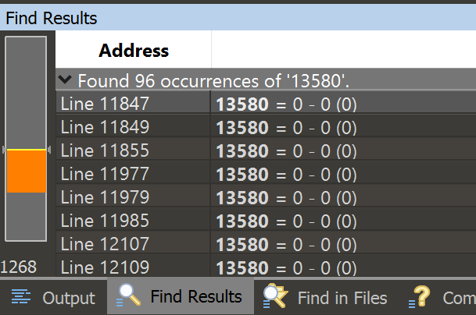

So I then started searching through the trace to see how the number being checked is built. This resulted in a few interesting things. The first reference to 224767 is 13580 = 220926 - -1 (220927). I decided to then find references to the index 13580, to see where the first reference is so I can then see how the number is built.

Turns out that this index is referenced in the gap we saw earlier. A good indicator we are on the right track. After going through the trace I find the algorithm is ((code(char) * 15) * 128 + 127).

Trying to solve for 224767, though is impossible, so there must be something missing. I then run the VM for input st and look for references to 2208010. I see 13580 = 220810 - -1 (220811). Which is different than what we had for just input s. Looking at the difference it is 116, which happens to be the ascii code for t. To make sure this was the last bit, I used input stt and the same number was there.

This means that the flag is broken up into sections of 2 chars and encoded as ((code(char_1) * 15) * 128 + 127) + char_2.

Using this knowledge I wrote a short program in c++ to decode each encoded char pair, one thing to note is the last letter is encoded as ((code(char_1) * 15) * 128 + 127), since there is no char afterwards.

int _tmain(int argc, _TCHAR* argv[]) {

int encoded[20] = { 0x35e8a, 0x2df13, 0x2f58e, 0x2c89e, 0x3391b, 0x2c88d, 0x2f59b, 0x36d9c, 0x36616,

0x340a0, 0x2d79b, 0x36d9c, 0x36616, 0x340a0, 0x2d79b, 0x2c89e, 0x2df0c, 0x36d8d, 0x2ee0a, 0x331ff };

for (int index = 0; index < 20; index++) { // loop through encoded chars

for (int char_1 = 32; char_1 < 127; char_1++) { // loop through ' ' - z for char 1

for (int char_2 = 32; char_2 < 127; char_2++) { // loop through ' ' - z for char 2

if ((((char_1 * 15) * 128 + 127) - char_2) == encoded[index]) { // checks if chars encoded against encoding found in binary

std::cout << char(char_1) << " " << char(char_2) << "\n";

}

}

}

}

system("pause");

return 0;

}

This finally resulted in the flag subleq_and_reductio_ad_absurdum, which you then add the @flare-on.com to for the final key.